"...a new study suggests that spoilers can actually increase our enjoyment of literature. Although we’ve long assumed that the suspense makes the story — we keep on reading because we don’t know what happens next — this new research suggests that the tension actually detracts from our enjoyment.

The experiment itself was simple: Nicholas Christenfeld and Jonathan Leavitt of UC San Diego gave several dozen undergraduates 12 different short stories. The stories came in three different flavors: ironic twist stories (such as Chekhov’s “The Bet”), straight up mysteries (“A Chess Problem” by Agatha Christie) and so-called “literary stories” by writers like Updike and Carver. Some subjects read the story as is, without a spoiler. Some read the story with a spoiler carefully embedded in the actual text, as if Chekhov himself had given away the end. And some read the story with a spoiler disclaimer in the preface."

So mysteries where you can deduce the ending with a practiced eye; or lets say, adaptations of famous tales where you can observe patterns of a recognizable myth or event are popular. Take ripped from the headlines procedurals like Law & Order and remakes of famous films; are enjoyable even though you know how they'll likely turn out.

I know Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, absolutely delighted me when it hearkened directly back to the Conan Doyle Canon, even though most of the movie diverges, creating its own Holmes and Watson in the process.

Two suggestions from this Wired Article offer interesting insight into this phenomenon

"Just because we know the end doesn’t mean there aren’t surprises. Even when I cheat and read the final pages first, a good thriller will still surprise me with how it gets there. Perhaps we’ve overvalued the pleasure of the shocking ending at the expense of those smaller astonishments along the way. It’s about the narrative journey, not the final destination, etc. Christenfeld and Leavitt even speculate the knowing the ending might increase the narrative tension: 'Knowing the ending of Oedipus may heighten the pleasurable tension of the disparity in knowledge between the omniscient reader and the character marching to his doom.'"and,

"Surprises are much more fun to plan than experience. The human mind is a prediction machine, which means that it registers most surprises as a cognitive failure, a mental mistake. Our first reaction is almost never “How cool! I never saw that coming!” Instead, we feel embarrassed by our gullibility, the dismay of a prediction error. While authors and screenwriters might enjoy composing those clever twists, they should know that the audience will enjoy it far less. The psychologists end the paper (forthcoming in Psychological Science) by wondering if the pleasure of spoiled surprises might extend beyond fiction:

'Erroneous intuitions about the nature of spoilers may persist because individual readers are unable to compare between spoiled and unspoiled experiences of a novel story. Other intuitions about suspense may be similarly wrong, and perhaps birthday presents are better wrapped in transparent cellophane, and engagement rings not concealed in chocolate mousse. '"

“Plots are just excuses for great writing.

What the plot is is (almost) irrelevant. The pleasure is in the writing,”

“Monet’s paintings aren’t really about water lilies,”

Nicholas Christenfeld

UC San Diego professor of social psychology

Looking at this study, and the history of storytelling, there is definitely some truth there. We all know certain stories, and pull them into our own times and places and enjoy them again and again.

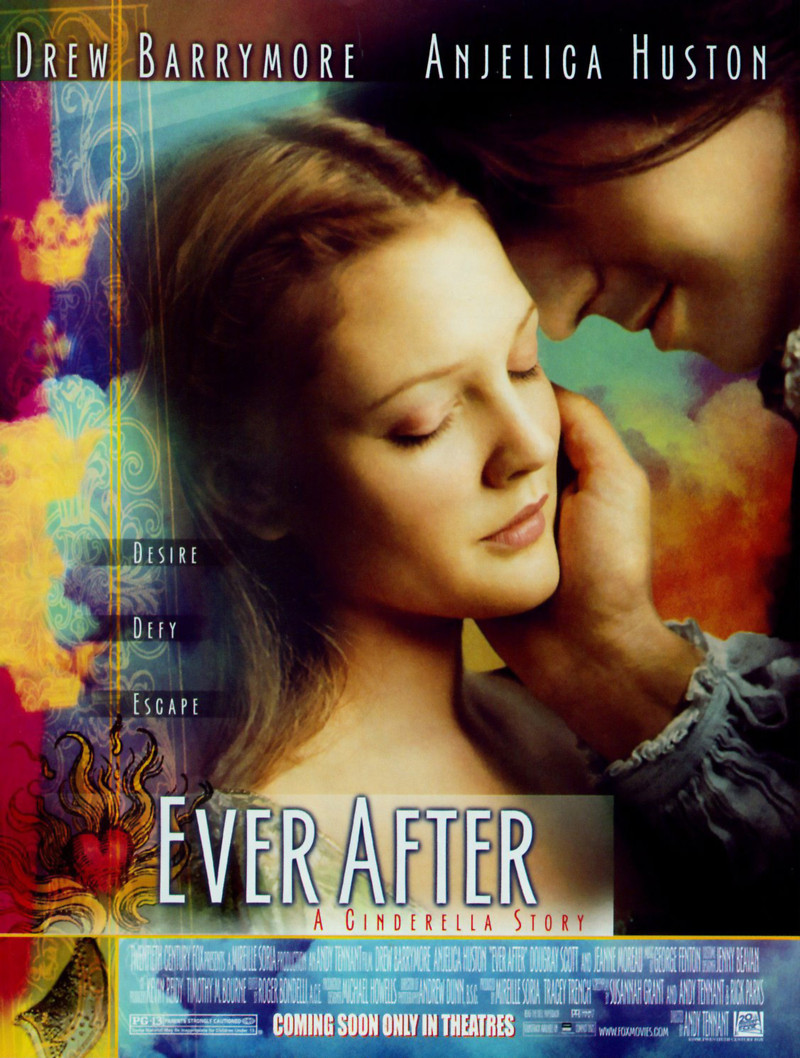

Just because we once had this–

Doesn't mean we wouldn't enjoy this, or that our children would.

2011 saw a spate of Fairy Tale adaptations, Red Riding Hood, Beastly, Once Upon a Time and Grimm

|

| Once Upon a Time |

Legendary seems to be banking on this fact with Jack the Giant Killer, which looks like it is going to be vastly entertaining, and If you like Brian Singer (I generally DO) you probably need to get over and residual fairy tale issues.

Facts are, a good story gets retold endlessly, how many times have parents cheated and abridged their way through a bedtime story? How many times have tales been retold through the years? What really makes an adaptation, retelling or reboot compelling is the artistry of the storyteller in this iteration, and the attention given to its execution.